Selling at school is more than just an exchange of products. For many students, it represents initiative, responsibility, and real-world learning. At The Columbus School, we promote the six Character Counts pillars: Trustworthiness, Respect, Responsibility, Fairness, Caring, and Citizenship. Student entrepreneurship reflects many of these values by encouraging these pillars in every sale.

Camilo Hoyos, Entrepreneurship teacher, strongly supports student business initiatives. “I absolutely love selling experiences. I love entrepreneurship and the initiative for students to make their own money,” he said. Although selling inside classrooms is not officially permitted, Hoyos believes it could be structured in a way that supports learning rather than disrupts it.

According to Hoyos, structure is key when integrating entrepreneurship into the school environment. He explained that selling could be allowed “Whenever the students are working on something independently or in teams, and it doesn’t require their attention to the teacher or to a presenter.”

In those moments, students would be able “to sell and buy.” His perspective connects entrepreneurship to life beyond school. “Literally, life is about selling. It is not only about products or services, but also selling your image, selling an idea.”

From his point of view, controlled and well-timed selling can be educational rather than disruptive.

Hoyos even suggests expanding the rules carefully. “I think they should also allow selling inside of the classroom but at a specific time, for example, during a brain break,” he said, adding that students could step out briefly if food is involved and then return to class. His comments suggest that selling could exist within clear limits while still respecting academic priorities. Revising the rules to allow structured opportunities could better align with the school’s emphasis on responsibility and real-world preparation.

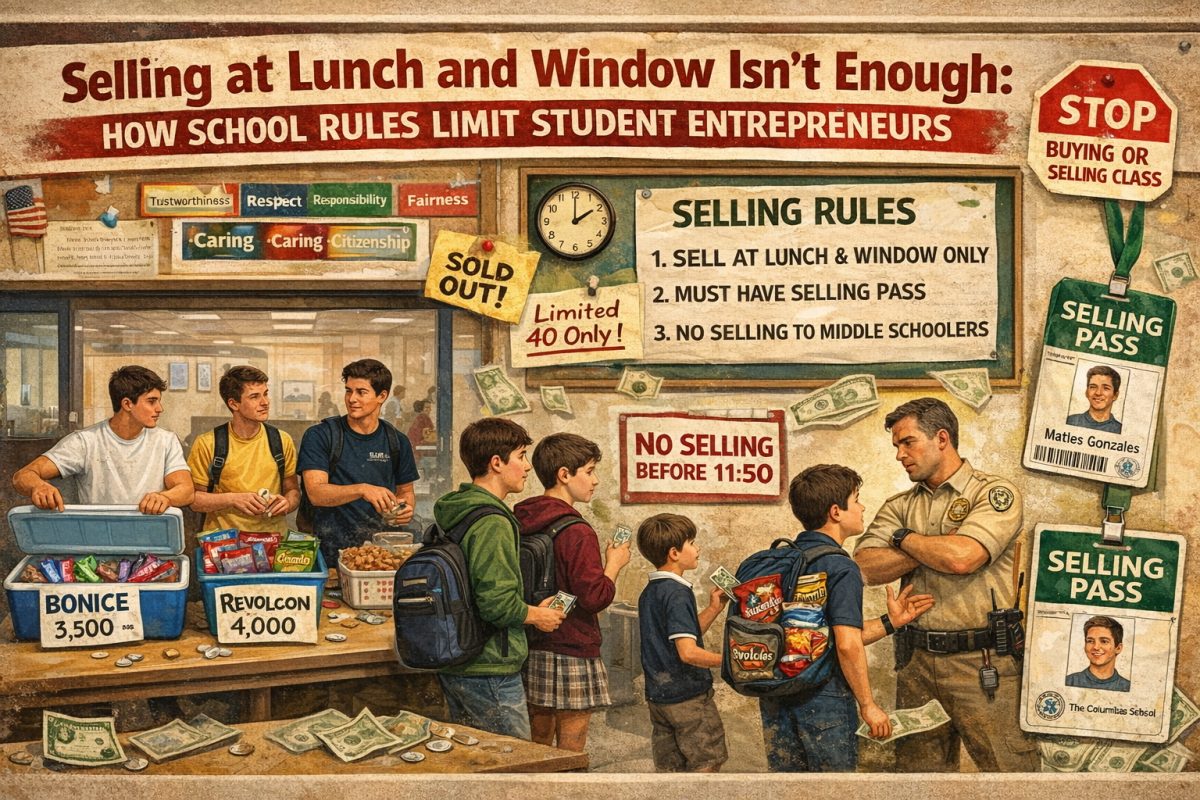

For student sellers, however, the current rules create practical challenges. Matias Gonzales, a 12th-grade student who sells Revolcon, explained how restrictions affect his business. “I think they should change the policy because my main buyers are middle school students, and they can’t buy during school hours, so I have to sell to them on the bus or while going home.” Because middle school students are not allowed to purchase during the school day, Matias loses access to a significant portion of his customers.

Logistics are another issue. “It affected me a lot because I have my product in my backpack, so I don’t take my backpack to the cafeteria, and I can only take a handful of product,” Matias said. Limited selling times and locations reduce how much inventory he can carry and how many customers he can reach. These restrictions directly impact how much he can sell during the short periods allowed. Still, his motivation remains strong. “It all starts with an idea, and if I can make the idea, I can become rich really young, like an eighteen-year-old millionaire,” he said. While the school may aim to prevent distractions, students like Matias see selling as preparation for future independence.

Martin Calle, also a 12th-grade student, shares similar frustrations. He sells Bonice and faces restrictions that prevent him from meeting demand. “I sell Bonice, and most of my clients are from middle school, and one of the rules of selling here in the school is that we can’t sell before or after school to middle schoolers,” he said. Even when students request products, he must decline. “Many people ask me if I can sell them Bonice before school, and I always say no because I can’t sell to them, and I’m losing money there.”

Time limits further complicate student businesses. “The window is like twenty minutes, and I need to offer around all the cafeteria, and that is not enough time to sell,” Martin said. Twenty minutes is a very short period to locate customers, promote products, complete transactions, and manage inventory. Such limited time makes it difficult to operate even a small-scale student business effectively.

Taken together, these perspectives suggest that current selling rules may need to be reconsidered. While the policies aim to maintain structure and fairness, they also limit opportunities for students to practice entrepreneurship within a supervised environment. Selling is seen by both teachers and students as a learning experience that builds responsibility, communication skills, and initiative.

If The Columbus School values real-world preparation and character development, administrators should review the current selling policy to determine whether structured, expanded opportunities could better support student growth. Thoughtful adjustments, rather than complete restrictions, may allow entrepreneurship to thrive while still protecting the academic environment.